Is Tom Wright’s ‘Paul’ convincing?

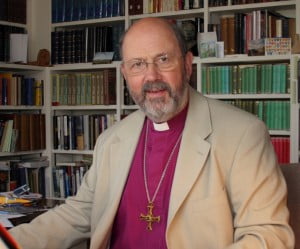

Tom Wright, erstwhile Bishop of Durham and Professor at St Andrew's, is often described as a 'leading New Testament scholar' in the world today. There is no doubt that he has significantly shifted the debates about Paul and his interpretation, and aslope that has (well-nigh uniquely) popularised his views on Paul and the balance of the New Testament through his shorter books and the remarkable '…For Everyone' series of commentaries, designed to do what William Barclay did for a previous generation. Every preacher needs to have this series on his or her shelf, not merely for the comments on the text, but for the examples of the style illustrations and stories are used to explore and explicate. At that place cannot exist many NT scholars who savour the level of acclaim from the perspective of local church ministry as that afforded by Stephen Kuhrt in hisTom Wright for Everyone.

Tom Wright, erstwhile Bishop of Durham and Professor at St Andrew's, is often described as a 'leading New Testament scholar' in the world today. There is no doubt that he has significantly shifted the debates about Paul and his interpretation, and aslope that has (well-nigh uniquely) popularised his views on Paul and the balance of the New Testament through his shorter books and the remarkable '…For Everyone' series of commentaries, designed to do what William Barclay did for a previous generation. Every preacher needs to have this series on his or her shelf, not merely for the comments on the text, but for the examples of the style illustrations and stories are used to explore and explicate. At that place cannot exist many NT scholars who savour the level of acclaim from the perspective of local church ministry as that afforded by Stephen Kuhrt in hisTom Wright for Everyone.

Whilst Tom has a wide following, his contributions to scholarly and to theological understanding are not always warmly welcomed. Conservatives in the United states (such every bit John Piper) have not thanked him for his criticism set out inJustification and elsewhere that much conservative evangelical theology of redemption is too rationalist and individualist, and offers a 'transactional' understanding of atonement which owes more than to mediaeval systems of honor than it does to the New Testament and its context. In similar vein, he criticises contemporary language of 'sky' every bit the place you get to when you die in his summary Grove bookletNew Heavens, New Earth. Information technology seems to me that on these points, Wright is offering a much needed corrective. His challenge is that conservative evangelicalism is oftentimes notalso evangelical, just not evangelicalplenty, in that it fails to allow its ain tradition to be reformed by a responsible reading of Scripture.

He has also had a mixed reception academically, just it is sometimes difficult to separate responses based on academic statement from responses driven past suspicion of what is felt to exist an apologetic or idealogical agenda. Mayhap the virtually bizarre was the contempo burst by Paul Holloway in protest at the award of an honorary degree from Holloway's institution Sewanee University. Nijay Gupta offers a helpful response to the personal set on that this involved.

A more serious critique comes in the form of a substantial review of Wright's Paul and the Faithfulness of God by John Barclay of the University of Durham. It has recently been posted at Durham Research Online and is due to be published in the Scottish Periodical of Theology.

A more serious critique comes in the form of a substantial review of Wright's Paul and the Faithfulness of God by John Barclay of the University of Durham. It has recently been posted at Durham Research Online and is due to be published in the Scottish Periodical of Theology.

Barclay does not pull his punches! He clearly dislikes Wright's rhetorical style, and thinks the piece of work is far too long and wordy. He is positive about Wright'south location of Paul in his historical and cultural context, though appears to consider there are others who do the same. Mayhap the nigh valuable matter nigh the review is that Barclay gives several helpful summaries of what he thinks Wright is aiming to exercise, including the aim of Wright's task:

At the cadre of Wright's thesis is a claim that Paul works with a set of interlocking narratives, arranged like a Russian doll, one inside the other (184). The outer frame is the story of creation leading to new creation, with humanity designed to be its rulers and its means of blessing. Inside this is the story of Abraham'due south family unit, which was intended to undo the sin of Adam and to put the creation project back on rails after the disasters of Genesis 1-11. Inside this again is the narrative of the Messiah Jesus, who takes on the role of Israel, where State of israel had failed in its task and when sin had used the law to concentrate its force in this ane place. Equally the representative Israelite (and every bit God himself, 'returning to Zion' in the person of his Son), Jesus fulfils the faithfulness that Israel was unable to accomplish, defeating sin and saving Israel while doing State of israel's job of saving the nations, so that those 'in Christ' (that is, in 'the Messiah-and-his people', 17) can proceeds the virtues necessary to rule the earth in the renewed cosmos. The Messiah-people are justified (counted members of the covenant people) past religion, that is, by a faith/faithfulness that matches the Messiah'south faithfulness, which is itself the expression of God's faithfulness to the covenant. In this covenant-narrative non only are the various motifs in Pauline theology scooped upwards into a single, multilayered story, but scholarly dichotomies between 'justification past religion' and 'participation in Christ', and between 'salvation history' and 'apocalyptic', are overcome by their placement within a single overarching frame.

The range and ambition of this thesis is remarkable, and information technology is advanced with a thickness of reference to biblical texts that will appeal to many who are looking for new ways to integrate non merely Paul simply the whole drama of the Bible. But is it sustainable every bit a reading of Paul?

His main criticisms of this thesis is that is has trivial explicit textual support within Paul's writings, and little in terms of explicit parallel within offset-century Judaism. Barclay does find positive things to appoint with, and nonetheless consider's Wright's work worthy of significant attention:

If the central thesis of Wright'due south work is unlikely to convince most scholars, there is still much to be salvaged. At many points Wright illumines the coherence of Romans and properly emphasises the church and its practice equally the goal of Paul'southward theologising. He correctly insists that Paul does non propound an abstract soteriology, but his counter-accent on narrative is weakened by his failure to recognize the distinctive ways in which Paul tells narratives in the patterns of grace.

Barclay is not persuaded by Wright's reading of 'Israel' in Romans 11 (when is it referring to ethnic Israel, and when to God'south people both Jew and Gentile?) nor past his understanding of pistis Christou ('faith of Christ'; is this our religion in Christ and what God has washed through him, or his faithfulness in his covenant purposes towards us?). And he strongly feels that Wright does not read Reformation commentators carefully plenty and give them their due. Barclay's conclusion is both positive and negative:

My tone may seem unduly negative. There are many valuable passages in this volume, and its energy, breadth, confidence and ambition are on a scale commensurate with its size. In the history of the discipline few scholars have attempted such an original even so comprehensive construal of Pauline theology, and in the modern era possibly merely Schweitzer could match the liveliness of Wright's listen. But I doubtfulness that many Pauline scholars will take the large synthetic schema that Wright presents, for all its attractions, while the stimulus offered past this book will be lessened, and perchance cancelled, by its persistently shrill and overheated rhetoric.

I accept a sense of feeling a trivial like a pygmy watching from the sidelines at these theological giants slugging it out in the arena of serious academic date. Similar many others, I accept found Tom'due south work to exist refreshing both in its engagement with history (particularly in The New Testament and the People of God) and its location of detail in an exhilarating summary of the 'big picture show' of what is happening in Paul and the wider New Testament. I must confess, though, to find him less persuasive in some of his detailed exegesis. Unlike Barclay, I practise get with his reading of Romans 11, though I was not persuaded by his reading of Mark 4, and found his commentary on Matthew 24 a little slippery.

I wonder if Barclay'due south review highlights something most the kind of projection Wright is engaging in. It has always made more sense to me to read his work as offer a theological interpretation of Paul, rather than a more than straightforward exegetical reading (Wright'south own protests notwithstanding). I constantly discover Wright's reading making a good deal more theological sense than many of the alternatives, even where some of the detailed exegesis might go awry. This so explains why, alongside his academic piece of work, he is able to speak and then effectively into the gimmicky pastoral scene.

I am not certain if Wright is planning a response to the review; I sincerely hope he is, and I am sure it will make fascinating reading.

Much of my piece of work is done on a freelance basis. If you lot have valued this mail, would you lot considerdonating £1.twenty a month to back up the production of this blog?

If yous enjoyed this, exercise share it on social media (Facebook or Twitter) using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo. Like my page on Facebook.

Much of my work is done on a freelance basis. If yous take valued this post, you can make a unmarried or repeat donation through PayPal:

For other ways to support this ministry building, visit my Support page.

Comments policy: Good comments that engage with the content of the post, and share in respectful debate, tin add together existent value. Seek first to understand, then to be understood. Make the most charitable construal of the views of others and seek to learn from their perspectives. Don't view debate every bit a conflict to win; address the argument rather than tackling the person.

Source: https://www.psephizo.com/reviews/is-tom-wrights-paul-convincing/

0 Response to "Is Tom Wright’s ‘Paul’ convincing?"

Postar um comentário